On 20 January 2022, The Lancet published a major study presenting the most comprehensive estimates of the burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to date. The study, led by the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) Project*, covered 471 million individual records or isolates, and used predictive statistical modelling to generate estimates of AMR attributed and associated deaths in 204 individual countries and territories, in 2019.

The results confirm what many of us have feared for a long time:

- In 2019, bacterial AMR directly attributed to the deaths of 1.27 million people.

- AMR is a leading cause of death worldwide, with the highest burden felt in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

- Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest death rate attributable to drug-resistant infections.

- The drivers of AMR are varied and complex.

- There are serious data gaps, particularly in LMICs.

The sobering numbers are undoubtedly cause for alarm, particularly as we continue to live under the grip of the ‘other’ pandemic, COVID-19, which will have potentially worsened the already dire trajectories of the so-called ‘silent pandemic’ of drug-resistant infections. The GRAM report shines a light on both the shocking impact that AMR already has, and the disastrous scenario we face if we continue to let the problem grow unchecked, allowing many bacterial pathogens to become even more resistant in the future, than they already are today.

On a more positive note, and if we apply our solution-focused lens, the numbers present many opportunities for building more coordinated and targeted interventions that could help to turn the tide.

ICARS key takeaways from the report

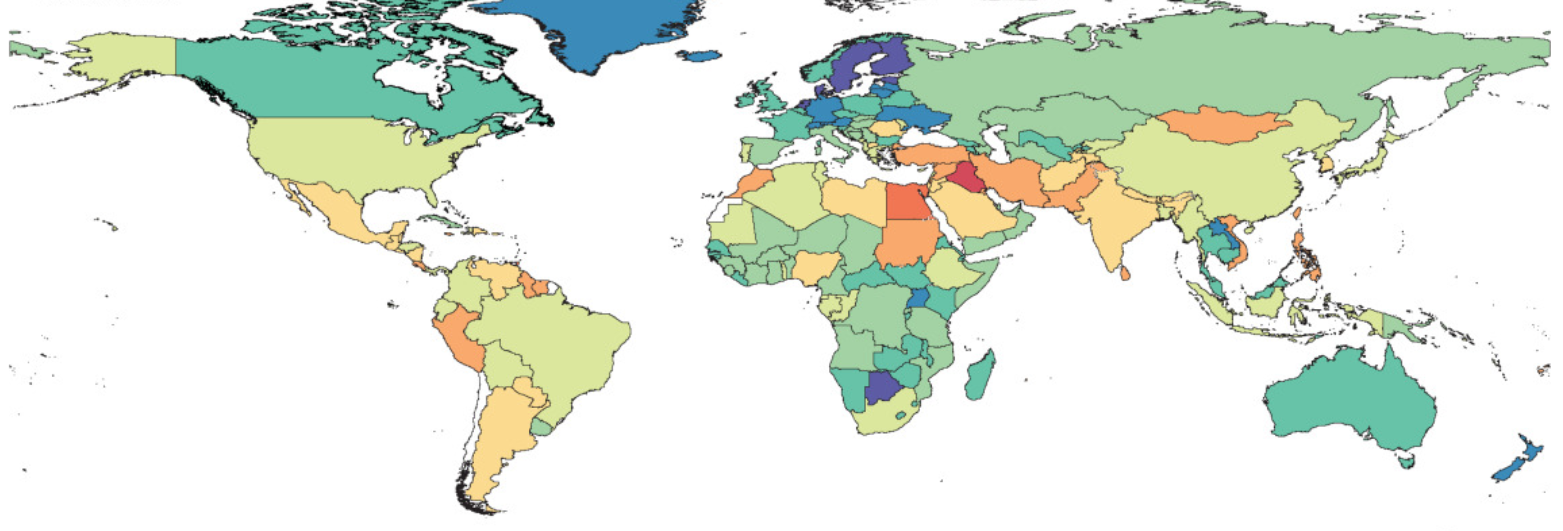

AMR is (unequally) everywhere

While for many years we have thrown around the figure ‘700,000 deaths caused by AMR each year’– the question remained, “where are people dying?” The granular data provided in this report confirms that drug-resistance is a problem everywhere, and proves that the biggest burden is indeed, in LMICs. We know, high AMR burdens are caused by both the prevalence of resistance and the underlying frequency of critical infections (such as lower respiratory infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections) which tend to be higher in LMICs. Given the strain that health systems already face in low-resource settings, and the fact that no access to antibiotics can be far more deadly than overuse of them, the need for context-specific interventions that address these multiple challenges is now more evident than ever before.

Regional variety calls for a varied response

While stewardship has been a focus of many national and international action plans, the findings of the report answer some questions about how efforts to tackle AMR could be more efficiently targeted. In western sub-Saharan Africa for example, increasing access to second line antibiotics could save lives, while in Southeast Asia efforts to regulate and reduce antibiotic use could be a more effective intervention. The report also points to the value of expanding infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, as a critical policy to tackle the deadliest pathogen-drug combinations. Other drivers of AMR the report covers are:

- limited laboratory infrastructure to perform microbiological tests that could both inform treatment or narrow antibiotics

- insufficient regulation that drives antibiotic use and ease of acquisition

- substandard or counterfeit antibiotics

- poor sanitation and hygiene

Knowing more about the drivers of resistance in particular settings, and the prevalence of specific resistant pathogens, means we can then tailor interventions to better meet those challenges.

Inaction is no longer an option

A key barrier to political commitment and allocation of national budgets is that AMR is often understood as a ‘future’ pandemic, that has been historically hard to quantify and place in the present, particularly on a local scale. These findings make it easier for decision-makers to understand that inaction is the more expensive option, and that AMR mitigation needs urgent political attention and funding.

“The weight of the scientific evidence is only growing, and so are the consequences of AMR for human and animal health. There is an urgent need to strengthen the efforts in low- and middle-income countries to develop and implement effective solutions to this global health problem. At ICARS, we welcome countries, organisations and foundations to join us in our mission to support AMR mitigation around the world.”

ICARS Board Chair, Henrik Wegener

Priority setting is critical

While most countries have National Action Plans (NAPs), the issue of how to prioritise AMR mitigation activities continues to be a big implementation barrier. These regional estimates empower local actors to understand where the biggest issues are and enable more strategic efforts to tackle them. A one-size-fits-all approach will not work. Instead, we need to come together to share local knowledge and best-practice and learn from the successes of others working in similar contexts.

AMR needs more airtime

A coordinated and multi-sectoral effort to address drug resistant infections, also relies on sufficient pressure from below. COVID-19 has shown the importance of global collaboration to tackle public health issues. While collaboration and coordination of the current pandemic at the political level have been challenging and at times insufficient, the innovative leaps and effective implementation of interventions have been most effective when sectors work together and mobilise resources and efforts towards the same goal, with the support of the public. The GRAM reports widespread media attention, will hopefully filter down into household discussions, classrooms and so on, leading to more awareness of the AMR challenge with people better understanding and advocating for action to tackle it. The role of advocacy and awareness raising is critical to shift AMR from being conceived as a distinct issue for microbiologists, to a societal challenge that poses a threat to the health of humans and animals, the environment, global food security and economic prosperity.

We must fill the data gaps and understand what lies beyond them

Major data gaps exist in many parts of the world, and while these estimates help to speculate on the drivers of AMR in settings with little or no data, it also makes evident the desperate need to fill those gaps. Knowing the accurate burden of deaths attributable to drug-resistant infections for each country, would be an important milestone that would both enable a more targeted response and indicate stronger global surveillance systems. But it is important to recognise that death rate data is only one perspective for understanding the burden of AMR. For low-income countries in particular, the excess/access narrative is a dramatic oversimplification. AMR exists within complex systems that precariously balance donor interests within under-resourced health systems, that limit health worker decision-making and reduce care options.**

ICARS invitation to partner is always open

Since 2019, ICARS has been working with partners in low- and middle-income countries to co-develop and implement sustainable, context-specific solutions to tackle AMR. By the beginning of 2022, we are proud to have already approved 9 demonstration projects, developed with LMIC government ministries, to tackle a specific AMR challenge across the One Health Spectrum. We are excited to move this data into action and continue to work with people around the world as they implement solutions to tackle this major public health threat.

Find out more about how you could join the ICARS mission here.

* GRAM is the flagship project of the University of Oxford Big Data Institute–IHME Strategic Partnership. GRAM was launched with support from the United Kingdom Department of Health’s Fleming Fund, the Wellcome Trust, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.